Highly promising methods for boosting efficiency – a compact guide for beginners.

When you first enter the world of lean production, everything might seem utterly confusing. This is mainly down to the terminology. There are more than a few acronyms and abbreviations and, more importantly, although a lot of the relevant concepts are well-known in Japanese culture there are few in Europe who are very familiar with them. Having practical definitions can therefore help you get to grips with it all. But this blog post isn’t – with the exception of the ever-present Muda at the end – about standard lean production terms. Instead, we’ve decided to focus on concepts that tend to be left by the wayside in comparison to other lean production methods. In the case of the first two terms, this is partially because they are extensions of lean ideas, which highlights just how important lean production has become for stimulating innovation in industry.

Achieving consistent capacity utilisation with ConWIP

ConWIP (Constant Work in Process) is a principle for controlling production that arrived on the scene in the 1990s. Developed by Wallace J. Hopp and Mark L. Spearman, the process isn’t one of the “classic” lean production methods, but does clearly share the same roots. Much like Kanban, ConWIP is a pull system. Its aim is to keep stock levels in assembly consistent and ensure a continuous flow of materials, without putting too much pressure on the work system.

Just like Kanban, ConWIP uses cards that contain information about the production order. There is one decisive difference between these two methods, however. Whereas a Kanban card only ever circulates between two consecutive workstations, in assembly operations organised according to the ConWIP principle, the ConWIP card accompanies the entire work order. Once assembly is complete, the card returns to the start for order management. Only then can the next order begin, meaning capacity utilisation is kept as consistent as possible.

Greater flexibility with POLCA

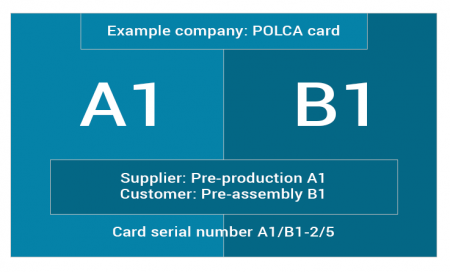

Short for Paired-cell Overlapping Loops of Cards with Authorization, the POLCA lean method is used where Kanban reaches its limits, which, as we’ve already mentioned, is the case in high-mix/low-volume operations. A particular characteristic of POLCA is that it features both push and pull elements. Specifically, the two following conditions need to be met before an order can begin:

- There must be a POLCA card (= pull element)

- The set start date must have been achieved (= more of a push element)

In practice, POLCA involves allocating different cells to certain work stages for carrying out production tasks. Depending on the product, an order therefore goes through certain cells. During early-stage, approximate planning, related cells are combined into pairs or loops. Each loop is then assigned a certain number of POLCA cards for a set period of time. These cards are pinned to the POLCA board for the relevant cell loop.

As tasks are carried out, the cards are passed on and subsequently returned. Let’s assume, for example, that a loop comprises assembly cells A and B with multiple consecutive work steps. Once work has been completed at cell A, the card together with the order (i.e. the material) is passed on to cell B, which then transfers it back to A once its work has been completed. If there is no card, work on the order can’t begin.

Key features of the POLCA method

Rather than being printed on POLCA cards, start dates are recorded in an ERP system or stored in the cell as an ERP print-out, for example. As a result, POLCA cards are kept relatively neutral – they only symbolise whether there’s free capacity at the next cell and aren’t assigned to one specific order. The advantage of grouping cells together is that operations between them flow smoothly, ensuring a short throughput time. It thus becomes altogether even easier to plan resources.

However, stock levels are not kept consistent, as they are with Kanban and ConWIP, which only allow production to begin once stock has been processed. By contrast, POLCA allows production to begin only once capacity – in the form of a POLCA card – becomes free in the next cell. In all three, the focus is on trying not to overload the system, which would lead to long order lead times.

The world of lean production

Less waste and more added-value – lean production methods let you make targeted improvements to your production efficiency. Our white paper provides a compact introduction.

.

Avoiding specific errors with Poka-Yoke

The very idea of continuous improvement sums everything up neatly – you can never achieve absolute perfection, but that’s no reason to stop trying. Instead, lean production is always about shortening throughput time, which is also an aim of Poka-Yoke – a lean production term made up of the Japanese words for “unfortunate/coincidental errors” (= Poka) and “prevention” (= Yoke). Poka-Yoke increases awareness of typical errors and identifies ways to deal with them effectively. There are various tools that can be used, including technical devices, checklists and coloured markings. Besides allowing companies to optimise existing processes, those with sufficient experience can anticipate where errors are likely to arise and take countermeasures early on.

It is also important to differentiate between hard and soft Poka-Yoke. Hard Poka-Yoke are measures that prevent errors. Take a cash machine, or ATM, for example – it only issues your money when you’ve taken your card out, which stops you walking away with your money and leaving your card behind. An example of a soft Poka-Yoke, in contrast, is the thermal spot you often find on frying pans. Once the pan reaches the perfect temperature, the pattern disappears and the spot turns completely red, helping you avoid the most common mistakes when pan-frying food. All the same, it isn’t impossible to make a mistake – the pan can still get too cold, or too hot.

7 Muda – knowing and tackling types of waste

Muda (“useless activity”) is without a doubt one of the most well-known lean production terms. It’s not uncommon for companies to focus too much attention on Muda and ignore Mura and Muri. This can cause problems in production. For instance, suddenly reducing your stock levels – say by introducing one-piece flow without making continuous improvements to the process – will not in any way boost efficiency. In fact, this would instead cause productivity to slump.

It’s important to remember here that Mura (“imbalance”) is essentially even more of a threat to production throughput time. In many cases, Muda even stems from Mura, which is why the latter is also referred to as the actual source of waste. Besides Muda and Mura, there’s also Muri (“overloading”). They are described collectively as the 3M and pinpoint non-value adding types of waste that increase production throughput time. But seeing as we’re just focusing on the aspect of waste at the moment, here’s an overview of the different measures you can take to tackle the 7 Muda:

Don’t move materials around needlessly: Bring workstations closer together. If possible, you should time and interlink work steps.

Reduce warehouse stock: Establish standardised and stable processes.

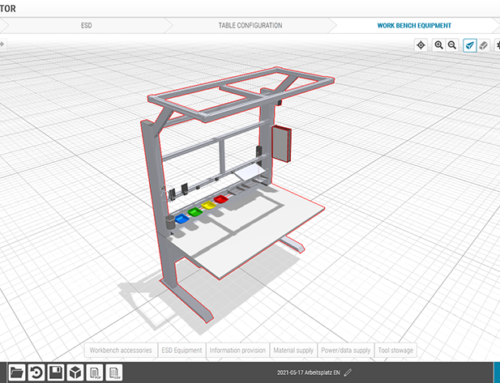

Avoid movements that are not ergonomic: Take the time to learn the basics of industry ergonomics and use an ergonomic work bench system.

Cut down on avoidable waiting times: Ensure your employees can work to optimum capacity, e.g. by using multiple stations.

Simplify processing: Pursue continuous improvement instead of getting too bogged down in non-functional details.

Overproduction: Embrace the pull principle (see above) and align your process chain with the customer takt time.

Continuous improvement: Always be open to trying out potential methods to improve and never be content with the status quo.

Are you interested in fascinating reports and innovations from the world of lean production?

Then we have just what you’re looking for! Simply subscribe to the item blog by completing the box at the top right!